The term ‘breakaway rebel competition’ is synonymous with rugby league, somehow permanently ingrained in the DNA of the code since its initial split from the 15-a-side game in 1895.

The term has popped up again this week following the ongoing stoush between the NRL and the RLPA. This comes almost exactly 25 years after a truce between the ARL and News Ltd brought about an end to the Super League war, while in more recent times battles have raged on the international scene for control of rugby league in Tonga and Greece.

However, even as far back as 1948, the batons were out over a plan to revolutionise the sport, as a rebel competition termed ‘Night Football’ threatened to tear the game apart.

On the 30th of May, 1948, an advertisement appeared in Sydney’s Truth newspaper for a rebel night rugby league competition to run between October and April. With rules tweaked to supposedly make it “the fastest game played by man afoot,” it would be run by none other than the mercurial former rugby league administrator, Horrie Miller.

Serving as NSWRL secretary for over 30 years and being credited with coining the slogan “The greatest game of all”, Miller had been unceremoniously dumped from his role in 1946, following a board-instigated investigation into an administrative matter.

It was at the beginning of September that more details on the rules of Night Football came to the fore. The new code, to be contested in the summer months under lights, would see teams consisting of 12 players and seven reserves fighting for possession of a round soccer ball over the course of four 20-minute quarters.

Scrums would be done away with completely and a line-out would be taken if the ball was put into touch, while an AFL-style bounce would restart play following a knock-on. Three players were allowed to stand offside during a bounce and two after a penalty kick had been awarded.

(Photo by J. A. Hampton/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The value of a goal was reduced to one point and the ball could be rolled for the kick. AFL players, footballers and even Olympic athletes were said to be in Miller’s crosshairs for potential recruitment.

To say that the competition was to be run by Miller would be true in the most literal sense; it was reported that Miller would serve as the selector, player registrar, head of referee appointments as well as run the protest and appeals board of the new code.

Displaying a cognisance many of his predecessors have since failed to grasp, The Sun reported: “Miller says he decided to take all the jobs because his experience with the league showed him the futility of trying to work with others.”

NSWRL administrators, with the mass defections from rugby union to league still in living memory, were cagey about the Night Football proposal, to say the least.

While AFL and football officials were quite happy to let their players do as they pleased in the off-season, rumours circulated that any of their rugby league counterparts found participating would face disqualification, potentially for life.

Miller raised the stakes by claiming that he had 600 rugby league players ready to take part in his new code and that he was “entitled to call it Rugby League because New South Wales Rugby League has never registered itself or its game.” First-graders could reportedly earn a generous sum of £13 for a win.

The unfortunate reality for Miller was that few, if any, first-graders were enticed, at least publicly, to jump ship.

Nevertheless, Night Football officially kicked off on a chilly September night at the Sydney Sports Ground with 1000 spectators admitted for free to see a couple of anonymous junior sides do battle. The evening would play out in bizarre fashion in more ways than one.

The Sun reported that almost no one – the spectators, the players, nor Miller – had much of an idea of the rules, with the players themselves given a quick run-down shortly before kick-off. While this might have given the referees a bit of leeway from the usual heckling from fans, the match officials involved still had other issues.

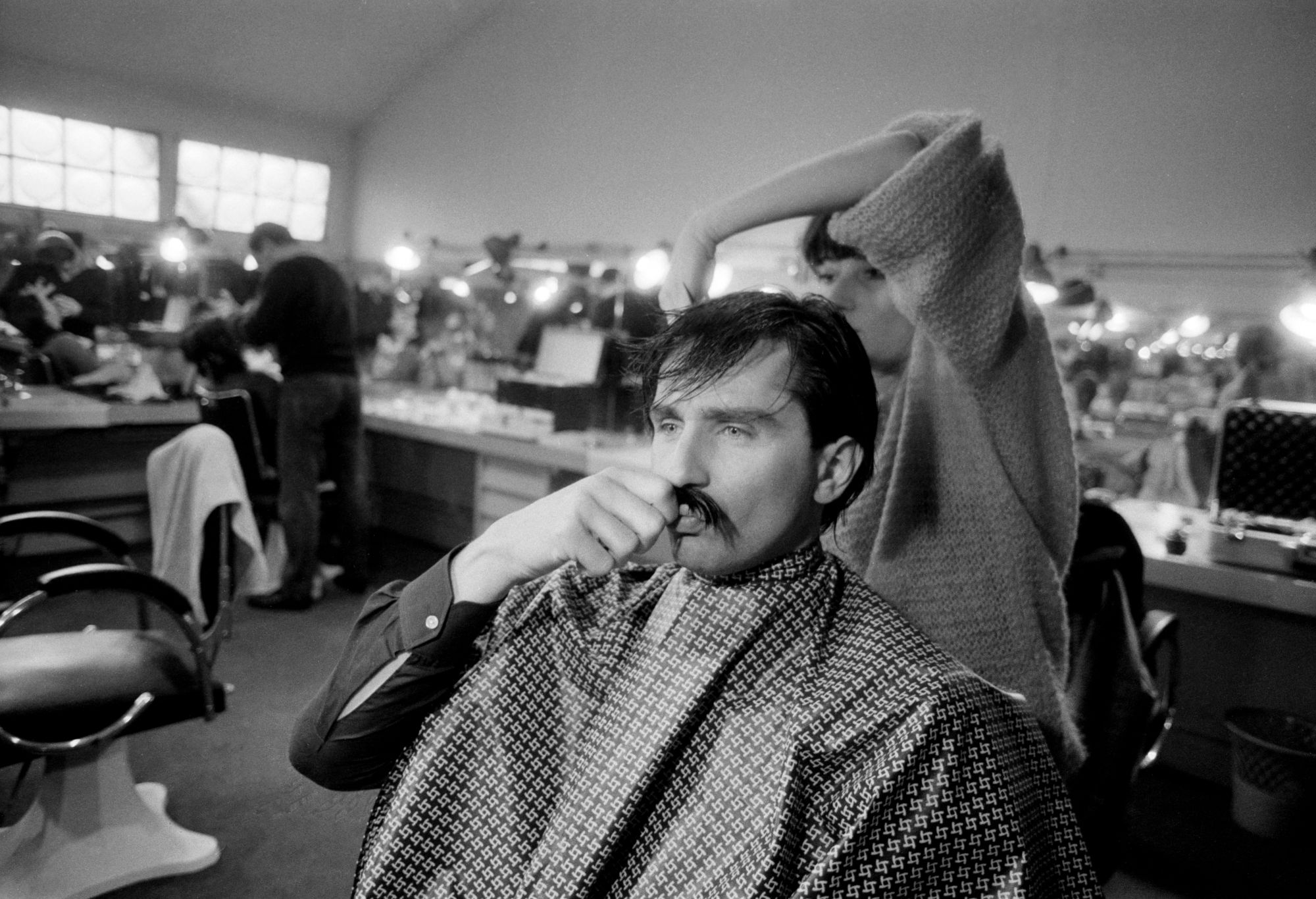

Fearing sanction by the rugby league’s board of control, prior to the match Miller had proposed that those involved could “wear a mask, grow a moustache or a beard” if they wished to protect their identity. The referees opted for the former, but found them uncomfortable and promptly did away with their disguises.

(Photo by Bertrand LAFORET/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

The sub-par lighting made it even more challenging for spectators to make sense of proceedings, with the players’ darkly-striped jerseys almost impossible to make out. Meanwhile, the new rules certainly had the effect of increasing the pace of the spectacle, but the unintended consequence was that a spate of injuries quickly followed. 11 players required treatment, with four knocked out from stiff-arm tackles, which were permitted in Night Football despite being banned in both league and union at the time. Two others were treated for exhaustion.

Unfortunately, things didn’t get much better for Night Football in the following weeks. 500 spectators who turned up for the next set of fixtures on the 7th of October expecting another night of complimentary entertainment, were less than impressed to find that an entry fee had been imposed, prompting many to boycott proceedings.

At the same time, the players who took part – just about all of whom were lower graders – were forced to do so under pseudonyms to avoid possible sanction from the NSWRL.

The visibility of the ball was an ongoing headache with different coloured balls found to make little headway. Miller was said to be keenly following the progress of Miklos Szabados, a prominent Hungarian-Australian table tennis player of the time, who had been using a phosphorus-coated ball to practise in the dark. The issue of player safety also continued, when on 14th of October no less than seven players were injured, with Western Suburbs and Balmain recording victories before a miserly 100 spectators.

Matters then reached high farce a couple of weeks later, when the players from Easts, scheduled to play against Wests as part of a double-header, decided to bail on their clash at the last minute to attend a local ball instead. By that stage it was too late to arrange a replacement team, so only one fixture could go ahead on the night, with a healthier 500 spectators in attendance to see Balmain – who were unable to field a full team – put on a decent spectacle to down Newtown.

CLICK HERE for a seven-day free trial to watch the RLWC on KAYO

At the start of November, the NSWRL opted to back up its threats and began proceedings against players and officials involved in Night Football. Despite earlier claims from an official that the league was “not being vindictive,” President Harry “Jersey” Flegg made his intentions patently clear when he blustered that “anyone who has been a traitor to the league will go.”

Former referee and Referees Association life member Joe Moses was set to be issued with a ‘please explain’ for his role in commentating on Night Football matches. But Flegg needn’t have bothered. Ultimately, the lack of quality athletes, poor gate takings and spiralling costs made the situation untenable for Miller, and it was announced on the 14th of November that the Night Football experiment was over.

In a final act of recompense, the following weeks saw league power brokers move to take down all photos of Miller from the hallways of the league’s Phillip Street headquarters. This was in spite of public objections, most notably Easts President Wally Webb, who was determined to see the decision regarding one of his club’s founding fathers repealed.

Despite directives issued by the league for the clubs to investigate player involvement in Night Football, the clubs dragged their heels and the matter was pushed into the too-hard basket after the dust had settled. Miller’s involvement in the game he had helped nurture from its earliest days, however, had come to an unbefitting end.