Keen cricket followers will already know what this article is about, simply by its title. Seventy-five years ago, on Saturday 14 August 1948, the most famous zero in the history of cricket was made.

In the long history of Test cricket, almost 10,000 ducks have been scored by more than 2,200 different players. Almost every one of them has been relatively forgettable.

But this one has become an iconic moment in Australian sport, the dismissal that generated a number, stated always to two decimal places, that every lover of the game instantly recognises.

What differentiates this duck from the others is the identity of the batsman, the timing of his innings, and its unique effect on his final average. Those circumstances will never, ever be repeated.

The tour

Australia had not toured England for a decade. Both nations were rebuilding after WWII, in cricket just as in every other aspect of life. The 1948 tour had a strong goodwill element, and attracted huge crowds and vast media coverage.

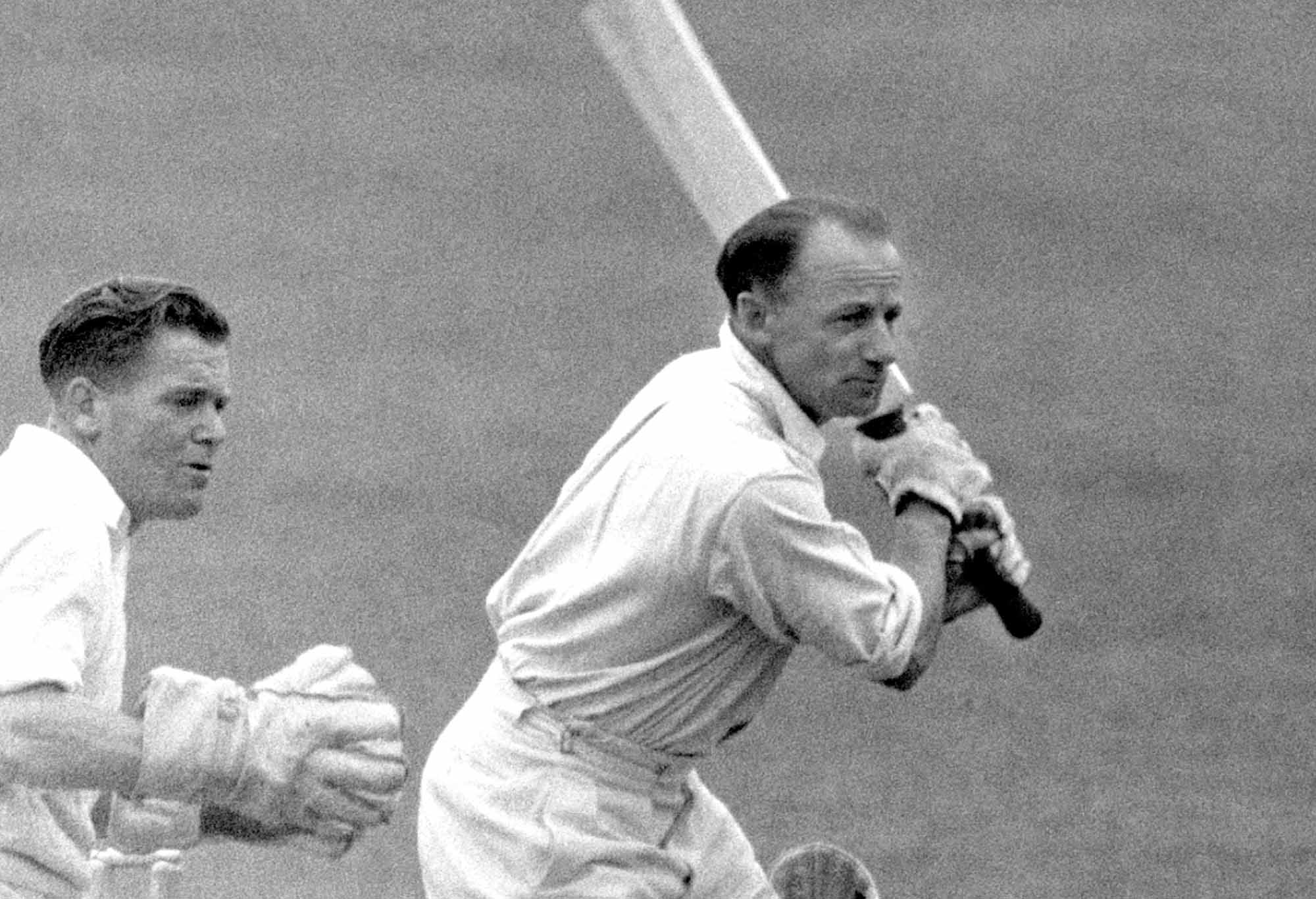

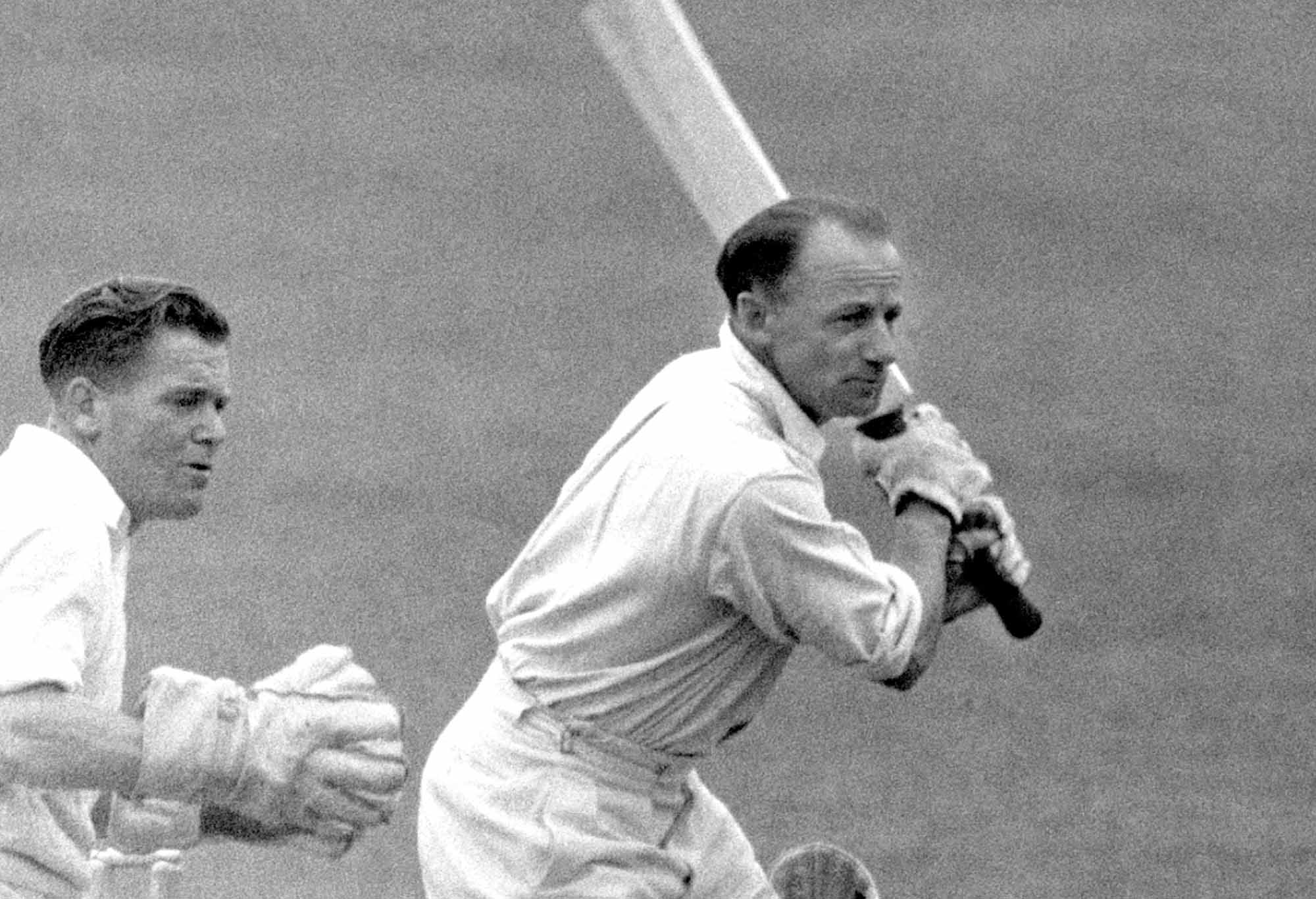

Although Don Bradman had lost some of his pre-war aura, he was still an imposing presence. Adding to public interest was that at 39 years of age, the tour would definitely be his last.

Sir Donald Bradman. (PA Images via Getty Images)

Notwithstanding a sense of personal obligation to English cricket, Bradman was bent on exacting revenge for numerous past slights. Australia had been outclassed 4-1 in his debut series, and again four years later by a Bodyline barrage directed at him personally. England then batted for three full days at The Oval in 1938, declaring at 7/903 only after Bradman and Jack Fingleton were injured and unable to take any further part in the game.

Bradman announced before departing Australia that he intended his side to remain unbeaten, and his approach to his objective was ruthless. The side won seven of its first eight matches by an innings, and scored 721 runs in a day’s play against Essex. Whenever opposing batsmen resisted for too long, he instructed Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller to attack them with bouncers.

Famed writer RC Robertson-Glasgow summed up Bradman’s approach as “Poetry and murder lived in him together. He would slice the bowling to ribbons, then dance without pity on the corpse.”

Manage, strategise & dominate. Download Wicket Cricket Manager today!

Unsurprisingly a number of team members, many of whom had served in WWII, did not particularly enjoy the tour. Miller later wrote that Bradman drilled into the side “When you get in front, nail ‘em into the ground. When you get ‘em down, never let up.”

The Australians’ match against Warwickshire, played shortly before the final Test, would prove noteworthy in one respect. Eric Hollies dismissed Bradman for 31 with a wrong ’un, and reportedly later told teammate Tom Dollery “I know I can bowl him with it, and I’ll give it to him second ball at The Oval.”

The innings

Australia went into the final Test at The Oval with an unbeatable 3-0 series lead, and an undefeated 26-game tour record. Despite those achievements, Bradman’s objective was not yet assured.

After the Test commenced late following wet weather, England was dismissed for just 52. Four of its batsmen made ducks and Lindwall took 6/20. Australia’s opening pair then added 117 runs to put Australian into a virtually unbeatable position.

The fall of Sid Barnes’ wicket brought Bradman, playing in his last ever Test match, to the crease. He would have felt confident of a large score given that his preceding Test innings was an undefeated 173 at Headingley in a record 404-run chase. Further, his previous three Test innings at The Oval had realised 232, 244 and 77.

The entire crowd applauded, and sang “For he’s a jolly good fellow.” England captain Norman Yardley instructed his team to give Bradman three cheers, then added “But that’s all we’ll give him- then bowl him out.”

Bradman wrote later that “I dearly wanted to do well. It was not to be. That reception had stirred my emotions very deeply and made me anxious- a dangerous state of mind for any batsman to be in. I played the first ball from Hollies though not sure I really saw it. The second was a perfect length googly which deceived me. I just touched it with the inside edge of the bat and the off bail was dislodged.”

.

Those present were stunned by what had just occurred. They then cheered him all the way back to the pavilion. Hollies said to a teammate “Best f-ing ball I’ve bowled all season, and they’re clapping him!”

In the ground’s media area, former teammates Jack Fingleton and Bill O’Reilly burst out laughing. Whether their reaction was out of delight or a sense of irony, is open to conjecture. Certainly Bradman interpreted it as a continuation of disloyalty dating all the way back to 1932/33. Fellow commentator EW Swanton said later “I thought they were going to have a stroke- they were laughing so much.”

Whenever Arthur Morris was asked subsequently whether he had witnessed Bradman’s final innings, he would answer “Yes, I saw it. I was at the other end scoring 196.”

The statistic

Bradman’s batting average had peaked at 112.29 in 1932. It was still an imposing 102.98 at the start of the series, and 101.39 when he strode to the wicket at The Oval.

If the match was taking place today, the entire world would know that to end his career with an average of at least 100.00, Bradman needed to score 104 runs in Australia’s two innings, or just four runs in one innings. 75 years ago there was no such awareness, let alone anticipation.

Bradman’s second-ball duck reduced his batting average to a ‘mere’ 99.94. However, there still remained a means by which to reclaim a three-figure average. All that he needed to do in his side’s second innings was to score at least 104 runs if dismissed, or a mere four runs if not out.

Unfortunately there would be no such ending. Australia responded with 389 to the host’s meagre total of 52, then dismissed it for a second time for 188. Accordingly it won the game by an innings and 149 runs. The visitors did not have to bat again, and so the opportunity was lost.

What followed

Bradman was still determined that his side would be the first to complete a tour to England defeated. However after the final Test it had to play a further seven matches to complete its demanding 34-game itinerary. Its members had now been overseas for almost seven months, and understandably were tired and homesick.

Ruthless to the very end, Bradman played in all but one of those matches. In them he amassed consecutive scores of 65, 150, 143, 153 and 27, and then 123 not out in his very last innings on British soil. Nine days later, he celebrated his fortieth birthday.

The Australian team duly ended its tour with a further five victories by an innings, against Scotland (twice), Kent, the Gentlemen of England and Somerset, as well as draws with the South of England and HDG Leveson-Gower’s XI. As a result it established a unique unbeaten record, and has been known ever since as “The Invincibles.”

The figure of 99.94 has also been perpetuated, even outside the cricket world. The Australian Broadcasting Commission’s postal address is GPO Box 9994 Sydney NSW 2001, while its national switchboard’s number is 13 9994.

The figure also serves as a permanent reminder that perfection is unattainable.