MUST WATCH: JFM obliterates IPL bowling attack - even Bumrah! - for 15-ball 50... and keeps going

A six-laden, 27-ball 84 from Jake Fraser-McGurk to continue his outrageous debut IPL!

In the court of public opinion, it’s common for neutral or non-involved observers of a legal trial to take sides. To determine if you like, who is the underdog or downtrodden, and root for them accordingly.

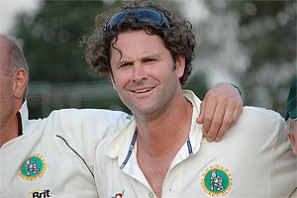

In the case of Christopher Lance Cairns however, currently standing trial in London accused of perjury, it is very difficult to find anybody to cheer for. Indeed, as the trial progresses, this seems more and more like one of those cases where everyone involved comes out a loser.

At the core of this case is the award, in 2012, of $950,000 in damages to Cairns resulting from a defamation case bought against former IPL boss, Lalit Modi, who claimed on Twitter that Cairns had been involved in match-fixing in 2008.

Cairns’ victory was to prove counter-productive though, as the evidence he gave at this trial in order to establish his case, opened him up to counter-attack from Modi and others involved, who had a different view of events.

The upshot was that British police were able to build a strong enough case against Cairns for perjury in the defamation case, and to bring him to account for his own actions.

The crown’s star witness is Lou Vincent, a right hand batsman whose 24-test career was marked by his debut Test in Perth in 2001, with a century and half century against a handy Australian attack including Glen McGrath, Jason Gillespie, Brett Lee and Shane Warne.

No matter what happens to Vincent from here, he at least knows that nobody can erase that performance from his record.

Whatever downwards trajectory Vincent’s career took after Perth, his evidence provides new meaning to the term ‘free fall’, his professional and private shame laid stark, public and complete.

Over a period of three days, Vincent’s testimony outlined his induction into Cairns’ deceitful web, chronicling non-performance and even ‘accidental’ performance, where on one occasion he struck successive boundaries despite doing his best to be dismissed.

Despite his complicity Vincent claims he never received payment or reward for his misdeeds, save for an occasion where a female escort was provided for his personal use at his hotel room. Who needs Ashley Madison when you can just conveniently miss a straight one?

With counsel for Cairns successfully painting Vincent as variously fragile, inconsistent, contradictory, delusional and a cheat, he remains a powerful witness – not least because Vincent seems happy to expose himself as all of those things.

Further, Vincent has neither sought nor been granted immunity from prosecution, thus his self-incriminating evidence carries more than enough weight to discomfort Cairns.

He presents as a man who has finally made peace with himself, ready to accept whatever consequence comes his way in return for cleansing his soul.

Vincent also claims that New Zealand bowler Daryl Tuffey was in on the scheme – perhaps not the strongest corroboration given Tuffey’s modest career record. If Tuffey was indeed on the take to bowl half trackers and juicy half-volleys, and he has not been charged nor called to give evidence, some may claim that it smacks of the conspirators paying for something they were already getting for free.

Current New Zealand captain Brendan McCullum’s evidence essentially supported Vincent’s take on things, outlining how he rejected an approach by Cairns to fix, whilst claiming that Cairns also told him that Vincent and Tuffey, along with a number of other big names, were in on it.

The problem for McCullum, or more particularly New Zealand cricket, is that there is a Test match against Australia due to begin in less than three weeks time.

Plenty has been made in the Australian press about the home side potentially going into the series undercooked, with only a one-day series and part of a Sheffield Shield game available before the first Test side is selected.

However concerning this might be, it is still far better preparation than hanging around in London watching rugby and being slagged as a liar in the witness box by Cairns’ legal team.

With a string of prosecution witnesses due to testify against Cairns, including Shane Bond, Daniel Vettori, Chris Harris, Kyle Mills and Andre Adams, New Zealand cricket has never before had their dirty washing so publicly on display.

In mitigation, none of the alleged offences involved matches where players were representing their country, but nevertheless, given that the core group of international players at any one time is so small, these events strike at the heart of New Zealand’s cricket credibility.

There have been other unseemly public spats, in 1986 for example when star bowler Richard Hadlee was on the wrong side of a team vote by 5-7 which demanded that he deposit proceeds from the sale of an Alfa 90 car he won for ‘man of the series’ in Australia, into the general team fund.

Hadlee resisted and the impasse was resolved only when the team backed down after public opinion swayed in Hadlee’s favour.

Or in 1994 when Stephen Fleming, Dion Nash and Matthew Hart were fined in the aftermath of a dope smoking incident whilst on tour in South Africa. They were seemingly penalised for being the only players to come clean about their involvement, while other participants who kept quiet escaped scot free.

But while these match fixing allegations are not earth shattering in the sense that Chris Cairns is not Hanse Cronje, captain of his country, they remain seriously troubling for New Zealand cricket authorities looking to build on the goodwill generated by the recent performances of the national side.

Cairns was a big fish in the little pool that is New Zealand cricket, a world-class all-rounder. At his best he was one of the most damaging and feared players anywhere, in all forms of the game.

Wherever the truth lies, whatever the outcome of the trial, enough has now come to light to paint Cairns in an extremely unflattering light. At worst he is a match-fixer and a cheat, at best he is a manipulator who has lost his reputation and the support of many previous close friends.

The final piece of this sordid jigsaw is Modi. However if he is expecting history to paint a kinder picture of him should Cairns be found guilty, he will be roundly disappointed.

All such a verdict will prove is that he was correct to call Cairns a match fixer, and that he should not have been found guilty of defamation.

But that alone is by no means sufficient to restore Modi’s reputation. A businessman with a chequered past, Modi was instrumental in the establishment of the Indian Premier League (IPL) in 2008, however in 2010 he was expelled by the BCCI, on 22 charges, before being banned for life in 2013.

Modi’s rap sheet includes conviction for conspiracy to traffic cocaine whilst a student in the USA, being pursued by Indian authorities for numerous instances of alleged financial irregularities, and being the subject of an Interpol investigation concerning political and financial corruption.

He lives in virtual exile in the UK, India’s own Julian Assange, admittedly with slightly more liberty and significantly more spending money.

In the superb 1996 Coen brothers film Fargo, police chief Marge Gunderson struggles to comprehend a scene where a kidnapped wife lies dead on the floor and pieces of one of the perpetrators extrude from the wood-chipper outside.

“And for what? For a little bit of money? There’s more to life than a little money you know. Don’tcha know that?”

Try telling that to Cairns and everyone associated with this mess.

There is so much money in cricket and gambling associated with cricket that, just like at this North Dakota log cabin, such a grisly outcome was probably inevitable. Make no mistake, whichever way this trial is finally concluded, there will be no winners.