Defying my predictions, the Atlanta Braves beat the Houston Astros to take the 2021 Major League Baseball (MLB) World Series 4-2 on Wednesday.

As the cricket season heats up, this seems a good point to bring to a close this series comparing cricket and baseball.

The previous article has links to the rest of the series.

Today’s briefly surveys how tradition has been a big part of both sports and how they have changed with the times in the face of financial and social pressures.

Cricket and national identity

In several countries, cricket came to occupy a key role in national life. While eclipsed by football in England, cricket remains valued as a uniquely English invention and institution, a village game adopted and championed by the elites as well as the burgeoning industrial working class of Victorian England.

For many cricket still represents a nostalgic, if outdated, image of England. Former Prime Minister John Major, who has written a history of cricket (More than a Game), waxed lyrical about Britain as “the country of long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pool fillers”.

In Australia, cricket also grew in popularity in the late Victorian era, as the colonies moved towards Federation, and commanded a place as the national game. One reason was the divided preferences among the colonies and their successor states for rugby and Aussie rules football.

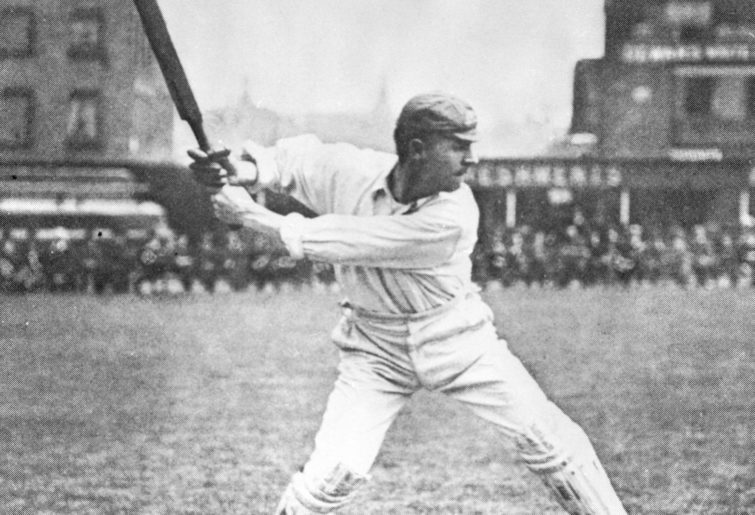

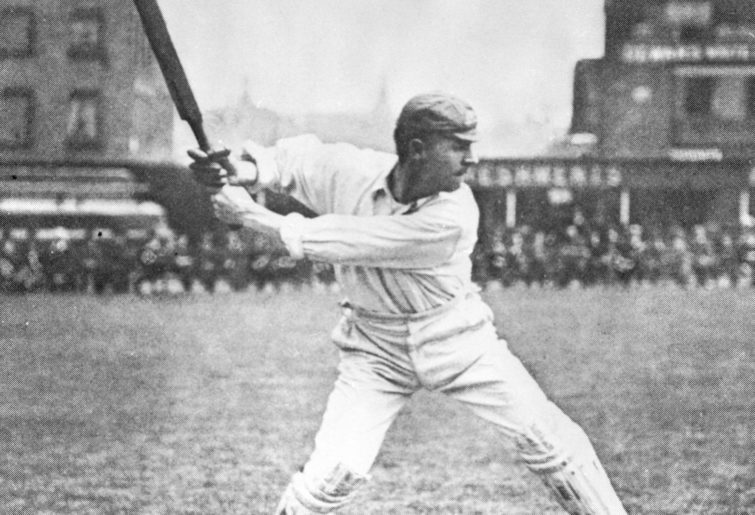

(Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Moreover, cricket was the first sport we played internationally, taking on England in an amazing 20 series in the 24 years before the colonies merged to form a new nation in 1901.

Australia only played one international football series of any code before federation – a British Isles rugby tour in 1899. The Australian players only came from NSW and Queensland and wore blue jerseys in Sydney and maroon in Brisbane.

Matching and sometimes beating the ‘Mother Country’ was a big boost for the national psyche as Australia came of age. In fact, Australia overtook England in Ashes Test wins in May 1921 (41-40) and has never been headed since.

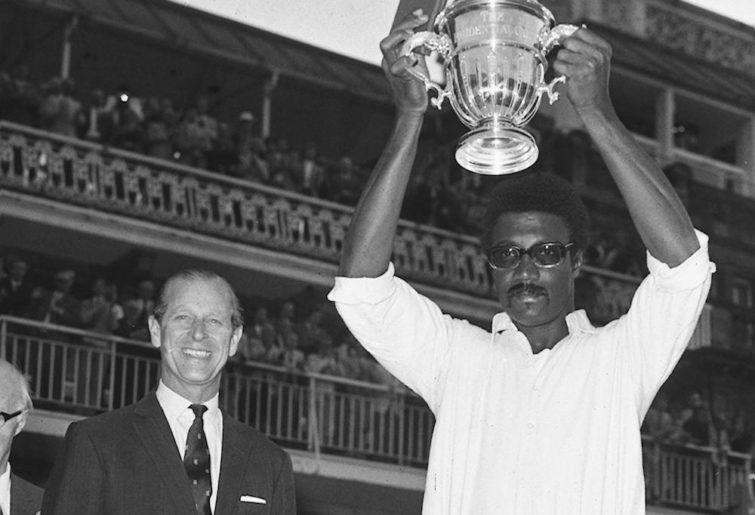

For the West Indies, cricket also had a big part in the coming of age of Britain’s Caribbean colonies, and became as an expression of unity among the constituent countries following independence in the 1960s, after failed efforts at establishing a Federation of the West Indies.

The Windies’ dominance in international cricket for nearly two decades from 1976 gave a huge boost to West Indian pride and identity.

International competition has been key to fostering cricket tradition has been. The Ashes and other series against the former colonial masters have been central in this.

Other rivalries such as the Frank Worrell Trophy, Border-Gavaskar Trophy, Australia-South Africa Tests and India-Pakistan matches have taken on a sharp edge at different times.

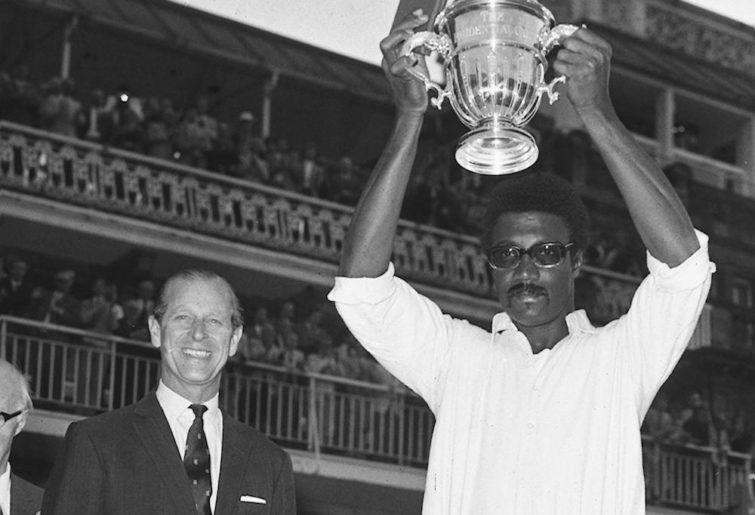

(Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

While cricket has declined in relative significance from its heyday in England, Australia and the West Indies, its growth on the subcontinent, particularly India, has more than compensated in terms of money, players and astronomical public interest.

Baseball and tradition

Baseball lacks the tradition of international cricket. As described in Part 2 of this series, competitions like the World Baseball Classic and the Olympics haven’t had much traction and pale into insignificance compared to MLB and the World Series.

US MLB teams are not representative in the sense of their players coming from their host city or state, and the players get traded from team to team at a great rate, especially since free agency gave players greater bargaining power from 1976.

Mid-season trading (as highlighted in the film Moneyball) is even more important than in football.

Four of the starting ten players in Atlanta’s World Series-clinching team were bought mid-season, when the team had not yet won 50 per cent of their matches. These four weren’t known as stars, but played crucial roles in the World Series triumph.

(Photo by Tom Pennington/Getty Images)

Nevertheless, tradition is a huge part of baseball and its place in American society, and of the product that is sold to fans.

Like cricket, baseball in America has a great love of tradition, with much discussion of the great players of the past, their statistics and exploits on and off the field.

Going to a ballgame and having a beer and hotdog is seen as part of the national fabric, one reason Americans still buy MLB tickets in such huge numbers – 69 million in 2019, nearly three times more than any other sports league in the world (and four to five times cricket’s total world spectator numbers at international, provincial and T20 matches).

The National League, one of the two divisions of MLB, was founded in 1876, one year before the first cricket Test and just after English county cricket started.

Baseball was known as America’s pastime, and its early years coincided with the US’s golden age of economic and population expansion in the late 19th century.

The World Series has been played since 1903 between the champions of the National League and the American League. By contrast, the US National Football League kicked off in 1920 and the National Basketball Association was only formed in 1946.

While the MLB teams has nearly doubled in size since 1901 and some franchises have moved cities, many of them date back to the 1880s, such as the Chicago Cubs, Philadelphia Phillies and Pittsburgh Pirates.

Uniforms and branding

Team uniforms reflect this fondness for tradition in baseball. While some MLB teams dabbled with more garish uniforms in the ‘70s and ‘80s, today they have reverted to a more traditional look, many of them predominantly white, or grey for away games.

The New York Yankees’ pinstripe uniform has remained exactly the same since 1936, in contrast to most ODI and T20I cricket shirts, which change every year. The Yankees don’t even have players’ names on their shirts.

Unlike cricket clothing, MLB uniforms in contrast are ad-free.

(Photo by Cooper Neill/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

In cricket, Test teams advertise beer, airlines, banks and the like on their shirts while IPL team uniforms are splattered with seven or eight sponsors’ logos, often for products like tyres, concrete, power cables and air conditioners.

The more things change?

Since the 1960s cricket has regularly introduced innovations around shorter games and faster scoring, prompted by concerns about the declining popularity of traditional red-ball cricket and the desire to attract new and bigger audiences, especially for television.

English county cricket first brought in 60-, then 40- and 50-over matches. The ongoing proliferation of formats in cricket has included T20, T10 and even T16.666 (also known as the Hundred).

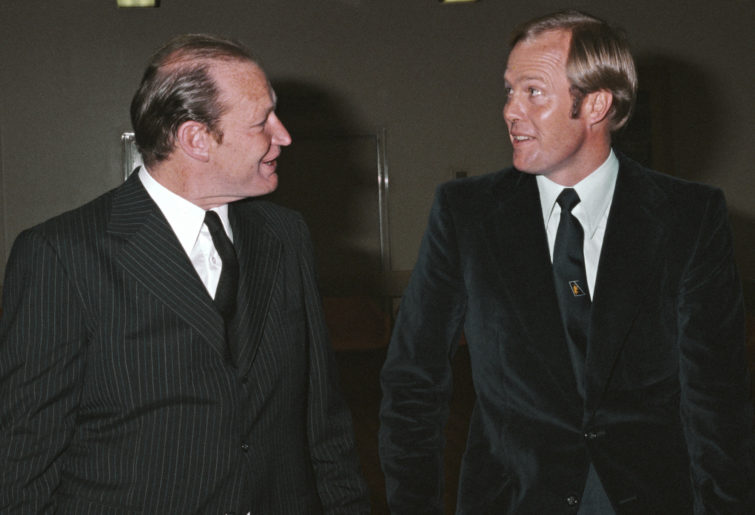

The commercial power of television flexed its muscles with World Series Cricket in 1977-79, ushering in a range of innovations.

(Photo by Allsport/Getty Images)

More recently, T20 as a TV product has brought franchise cricket to the fore, as in baseball, than representative or provincially based teams.

By contrast, MLB baseball has essentially been fixed as a nine-innings game since the 1890s. Its rules have also remained fairly static since 1901.

The biggest change was in 1920, using new balls whenever the ball got slightly worn, rather than just one throughout the game, and banning defacing the ball or applying foreign substances.

A couple of other changes, like lowering the height of the pitcher’s mound in 1969, and the use of a designated hitter in the National League (1973), were also aimed at reducing the dominance of the pitcher and getting more runs scored.

The growth in size of cricket bats over the last 20 years has boosted scoring rates, especially in white-ball cricket.

The length and width of baseball bats was fixed in 1895, with only wooden bats allowed in MLB.

Stats and umpires

The use of statistics is one area where cricket is catching up to baseball, particularly among professional teams, who are adopting some of the sabermetric methods pioneered in baseball.

Among fans, the fascination with statistics has been even more ingrained in baseball.

(Photo by Rod Mar/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Baseball statistics tend to feel a lot more robust thanks to the huge number of games played, all in one format (some batters have twice as many innings in a season than Sachin Tendulkar’s 329 Test innings in 24 years).

They reach a much higher level of analysis than in cricket and form a backdrop to baseball commentary to a much greater degree.

Umpiring in baseball hasn’t gone as far with technology and DRS-type replays, especially for decisions about whether the ball is in the strike zone.

TV replays often show that the umps get these wrong, but this is accepted more philosophically than cricket’s obsession with the tiniest margins, notwithstanding occasional heated arguments between managers and umpires.

Baseball – slower games and smaller audiences?

Despite its huge revenues and soaring player salaries, described last week, baseball has become concerned about declining interest in the US.

Television viewers and spectator numbers (down ten million annually since 2008) have declined steadily over the last 20 years. Baseball has lost its primacy as America’s game to gridiron, and lags basketball in media profile and public recognition of its stars.

A number of explanations have been advanced. The fan-base is getting older, with age of the average TV viewer increasing to 57 from 45 in 1995. Younger generations seem a bit less engaged with baseball, although this is a challenge for other big sports too.

A slower pace of play is also seen as a turn-off for fans, which sounds unusual given the average baseball game lasts about as long as a T20 match. But, for comparison, an average play-off game in 2021 lasted one hour longer than 60 years ago.

Changes contributing to longer games include the use of a battery of relief pitchers, whereas 30 years ago starting pitchers lasted late into the game and often pitched the full nine innings. Bringing in a new pitcher chews up extra minutes.

Sabermetric analysis has encouraged greater reliance on batters who can hit home runs but tend to strike out more often. As a result the ball is in play less often, with less action running between the bases and in fielding plays.

(Photo by Elsa/Getty Images)

So, unlike in cricket, emphasis on big hitting hasn’t made the game more entertaining. Likewise, the advent of harder throwing pitchers has also made it tougher to get the ball in play.

Final thoughts

Cricket’s very flexibility of format – present since the beginning – has allowed it to adapt to changing times and commercial pressures.

However, the challenge remains not to throw the baby out with the bathwater – so that traditional red-ball cricket, especially Tests, isn’t neglected and devalued, and T20 franchise cricket doesn’t crowd out international competition.

US baseball’s challenges are due not to any limits imposed by tradition so much as change and innovation prompted by the drive for team success, which have perversely made it less entertaining for some.

On a final note, I will bring up a pet peeve that suggests cricket is still some way behind baseball in professionalism.

(Gareth Copley/Getty Images)

I cannot believe that MLB managers would allow their fielders or pitchers to yell “catch it!” in the way that cricketers do at all levels when a ball goes in the air, even to slips. Or that commentators wouldn’t lambast them for it.

I am certain this almost automatic kneejerk reaction, which has crept in since the 1980s, has led to dropped catches on several occasions, without ever increasing the chances of a catch being taken. It reeks of an amateur era.

But I hope the overall comparisons have added some perspectives to how we see cricket.

I will follow up with a short article providing a summary table of the key metrics and points of comparison for those who prefer less long-winded pieces.

A look at baseball statistics and possible lessons for cricket, and how the two sports are portrayed in popular culture, might also be worth a look at a later date.