Bairstow goes ballistic, clubs 45-ball ton to spearhead highest T20 run chase EVER

Johnny Bairstow has hit his way back into form with a 45-ball century as he steered his side to a record-breaking win, easily chasing…

It was January, 1992. For more than a decade, the cricketing world had been ruled by pace, and in particular the relentless barrage of the West Indian fast men. Spinners were for subcontinental dustbowls and to bring on to give the pacers a rest, hoping they could sneak in a few overs without getting hit for too many. The days when slow bowlers dominated the wicket were long gone.

But Allan Border’s Australia, having risen from the depths to a new strength, were searching for that bit extra that would push them over the top, from a team that could beat up England to one that could compete with the Windies themselves. They came up with a quintessentially Australian answer – legspin – and a quintessentially Australian embodiment of the art.

In that Sydney New Year’s Test, a beefy kid with a terrible haircut shuffled nervously to the crease and sent down his first ball in Test cricket. He was overweight, he rolled the ball out of his fingers with no great energy or venom, and faced with the best players of spin in the world, he was taken apart. Ravi Shastri and Sachin Tendulkar splattered him across the SCG turf.

And yet…there was something there. Every now and then, a ball would kick and spit and fizz past the edge. Every now and then the Indian masters would be fooled. Those moments were soon lost amid the mounting of a big score – but they were there.

It was December, 1992. Hammered in his first two tests to the tune of one wicket for 228 runs, the beefy kid had been dropped, then popped up in Sri Lanka with a brief flurry to polish off an unlikely comeback victory, then been dropped again. But he was back, the Australian selectors still desperate for that elusive creature, a match-winning spinner. The first Test against the West Indies had been drawn, the Australian attack having the world champs on the ropes but finding themselves unable to land the killer blow. Maybe the blond could make that difference?

(Photo by Getty Images)

He’d lost weight. He’d cut his hair. Still he did little in the first innings to persuade anyone he’d come far from the Indian thrashing of almost a year ago.

And then.

In the second innings of that Boxing Day Test, the Windies were chasing a stiff target and doing it easily. Phil Simmons and Richie Richardson were cruising. It all seemed depressingly familiar.

Border brought on Warne.

The kid rolled up to bowl to Richardson and out of nowhere produced a creature rarely seen in the wild since the days of Benaud: the flipper. It skidded and crept low and cannoned into the skipper’s stumps. Richie walked off nonplussed.

From there the powerful West Indian batting lineup imploded. Shane Warne, January’s cannon fodder, had become December’s heavy artillery. He finished with 7-52 and a famous victory was won. Suddenly, unexpectedly, the key to world domination had apparently landed in Australia’s lap.

And from that point on…it was history made at every turn.

Australia didn’t win that series – the decisive blow was still delivered by pace and the terrifying form of Curtly Ambrose. But the first stone had been rolled down the mountainside, and the avalanche was now inevitable.

To those who were not there, who did not witness Warne’s explosion onto the world stage, it may be hard to fully understand how exciting it was. The electric thrill that shot through us all when we saw that indelible ball dip and rip and twirl past Mike Gatting’s solid, experienced bat and knock back his off-stump.

The tingle that ran down our spine as we saw Gatt walk off in utter bewilderment, not really believing it had happened. Somehow, the old English pro was thinking, the keeper has flicked the bails, or the ball ricocheted off him. I can’t have been bowled, he told himself, shaking his head, because cricket balls don’t do that.

Certainly, cricket balls delivered by a nervous pup bowling his first ball of his first over of his first Test match in this country don’t do that. But this one did.

Because that’s what Shane Warne did: he made cricket balls do things we’d never seen before. That we didn’t know they could do. And in doing it, he made our hearts race and our minds bloom with possibilities and brought forth roars from our throats like nobody else could.

When he flung the ball several miles outside leg stump, drawing the thrust of a contemptuous pad from Graham Gooch, only to see it float past that pad and screw back at an utterly impossible angle to clean bowl him…well. It’s one thing to watch sport played at a high level. It’s an entirely different thing to see a man defy the laws of nature.

He kept on doing it too, for years and years. Twelve years after Mike Gatting walked off flummoxed, Andrew Strauss did the same, with a similar expression of confusion, after Warne ripped one from wide outside off behind his legs, even as he walked across the crease to smother it. For 12 years everyone on the planet had known Warne could do it: Strauss still couldn’t stop him doing it, or understand how he did it.

For Shane Warne did something to the brains of calm, steadfast men. He scrambled their thoughts, caused warfare between their bodies and minds. His highlight reel is filled with those massive legbreaks, but he got as many, if not more, wickets with balls that went straight. Early in his career the flipper was a regular routine, skidding through to humiliate the batter who failed to read the signs. Later it was the “slider”, the innocuous delivery that evaded the bat or caught the edge by confounding expectations. But always it was deception and precision and the suffocating pressure of facing a bowler who tore up the legspinning rule book by turning the ball as far as anyone ever had while maintaining the nagging accuracy of a flat-darting offie.

Watching it was exhilarating. Many were brought to the game by the excitement of Warne’s theatrical artistry. Those of us who already loved cricket found a whole new dimension opened up. Old-timers wept with joy at the revival of an ancient art: newcomers shouted with delight at the emergence of a new one.

I took up bowling legspin. Pretty much every cricketing kid in Australia did. Even the team alphas who’d prided themselves on how fast they could hurl them down started looping up leggies in the nets. Some found their calling in the leggie’s art. Others – myself included – found that imparting spin to the ball while also landing more than one in six balls on the pitch was a lot harder than Warne made it look. But all of us were intoxicated by the mystery and the possibility of the art.

To be an Australian cricket fan in those days was heaven. Warne’s legend grew and grew, and the team that his arrival transformed evolved into a ruthless machine. He hurt himself, went under the knife more than once, and came back different but still irresistible. He kept on amazing all, demonstrating phenomenal stamina and grit along with his skill. In his twilight in 2005, he had his greatest series of all, almost dragging a sputtering Australian team over the line against a formidable English enemy on his own. He never stopped confounding expectations.

It was fun to see him, along with Steve Waugh’s world beaters, crushing all comers. It was inspiring to see him keep on taking bags of wickets, so often just after it seemed his time was up. But for pure, blood-stirring joy, nothing could compare to those first few years in the 90s, when he spun it a mile and made our jaws drop, when he introduced us to something so new and dazzling it could have been sorcery. Nothing matches the feeling of December 1992, when Richie Richardson’s stumps were rattled and everything changed forever.

Off the field he didn’t always show himself in the best light. His personal life became a soap opera. He made himself easy to criticise, both during his playing days and afterward. But like the rock star he was, once he stepped onto the stage and started playing his greatest hits, everything else melted away. You’d forgive him anything, for the beautiful music he made.

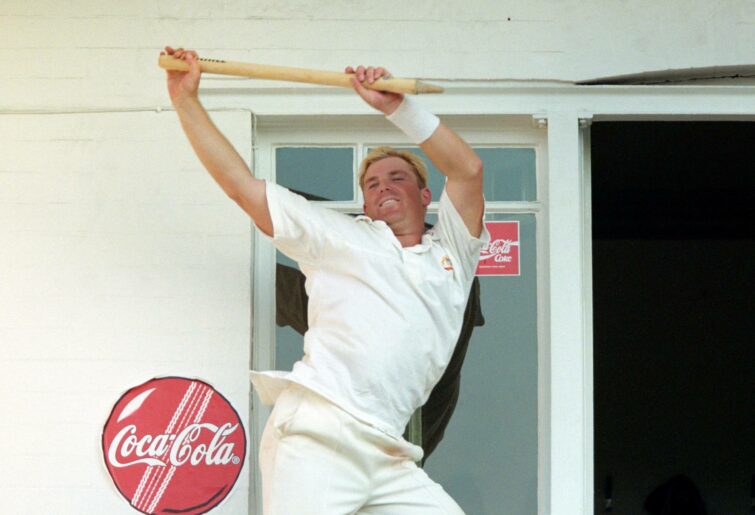

Shane Warne of Australia celebrates victory by dancing with a stump on the dressing room balcony after victory over England in the Fifth Ashes Test Match at Trent Bridge on August 10, 1997 in Nottingham, England Australia won the match by 264 runs. ((Photo by Clive Mason/Allsport/Getty Images)

Today is shock and grief and a struggle to process the loss. But amongst the sadness is something else, something that will only grow as the days go by, till it is the overwhelming emotion that remembering Warne inspires: gratitude.

For we were blessed to be born in a time that allowed us to see Shane Warne bowl. We will forever be thankful.